Many Australian investors have long been able to sleep comfortably at night owning large holdings in “blue-chip” Australian bank stocks which have delivered high fully franked dividends and share price appreciation over many years.

While Australian bank shares have done well for investors over the last 10 or 20 years, it appears to us often that many investors have come to associate the safety of having their money invested in a bank (in for example a term deposit) with having a large portion of their share portfolio invested in bank shares. As a result, in addition many Australian investors have taken comfort with their familiarity to the banks’ brands and large sizes – as demonstrated by the Commonwealth Bank’s share register which has in excess of 50% its shares owned by direct retail investors.

This lesson seeks to explain the risks investors should be aware of when owning shares in Australia’s big 4 banks.

Australia’s banks have benefitted greatly from Australia’s resilient economy of the last 20 years and their shares in total are now valued at around $400 billion – now making up one quarter of the market capitalisation of the entire Australian sharemarket. The growth in Australian banks’ profits has also been supported by the exceptional house price appreciation in Australian capital cities since the 1980’s. The median house price has risen from less than 3x the average income in the 1980’s to almost 8x today.

The fuel for this growth has been lower interest rates – meaning that most consumers have been able to borrow higher amounts of debt from a banking sector willingly providing credit for consumers to borrow and buy their own house or investment property. The emergence in the last 20 years of commission-driven mortgage brokers like Aussie Home Loans and RAMS has also helped allow the banks to grow their collective mortgage lending books up to almost $1.5 trillion – contributing greatly to the growth in the banks’ profitability over the last two decades.

While Australian banks fulfill many of IML’s criteria in terms of having strong competitive advantage and good recurring earnings, looking forward the Banking sector has particular risks that have to be considered when investing in them.

Banks are fairly highly leveraged companies and consumers are heavily indebted

The major Australian banks are highly leveraged companies with outstanding loans totaling $2.5 trillion, of which mortgages represent $1.5 trillion. Banks effectively borrow money from depositors and other sources, then on-lend money to customers to make a margin.

Regulatory reforms since the 80s such as the Basel 1 reforms introduced in 1988 allowed banks to “gear-up” their mortgage portfolios considerably, to the point where banks only needed to hold $20,000 in balance sheet capital for every $1m in mortgages.

This more accommodative regulatory environment, combined with a fall in interest rates from 17% per annum in the early 1990’s to 1.5% per annum today helped banks to leverage up and grow their mortgage books very strongly – which together with strong population growth led to house prices in Australia increasingly markedly.

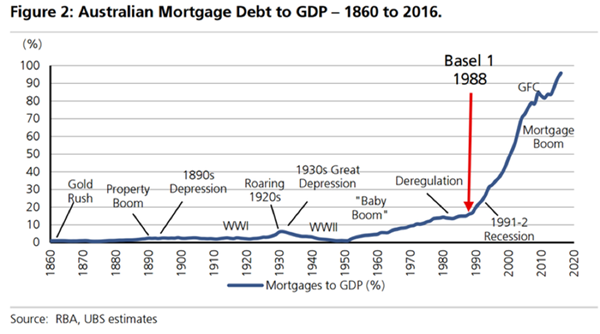

As seen from chart 1 below, Australian mortgage debt to GDP has risen to record levels since deregulation of the Australian banking system in the early 1980’s and the Basel 1 Accord in 1988.

Chart 1: Australian Mortgage Debt to GDP

Because of the large increase in borrowing of the last two decades, many Australian consumers now have limited capacity to take on additional debt with household debt almost 200% of annual disposable income which is very high compared to most other countries.

There is now the very real possibility that several of the drivers of the strong credit growth over the past two decades are now in reverse. Tightening capital requirements by regulators – as well as consumers who appear well saturated with debt – mean that credit growth going forward will, in all likelihood, not be as strong as it has been in the past. This will make it much harder for banks to grow their loan books and their profitability going forward.

Banks earnings are cyclical with exposure to the bad debt cycle

Australia now holds the world-record for the longest period of economic growth in history – that of 27 years. Because of this period of uninterrupted growth, many Australian investors may be excused for thinking that economic downturns or bad debt cycles are things of the past – unfortunately we believe this is wishful thinking.

Chart 2 shows the history of bad debt charges as a proportion of total loans for the major banks. In Australia’s last recession of the early 1990’s bad debt charges spiked upwards – this was disastrous for Australia’s banks with all of them having to cut their dividends and Westpac and ANZ both recording huge losses and having to raise capital. We saw another jump in bank bad debts charges for the banks during the GFC in 2008-2009 which again forced Australian banks to cut dividends as well as to raise new equity to replenish their balance sheets.

Chart 2: Major Bank bad debt charges as a % of loan book

Source: RBA 30-Sept-1979 to 30-Sept-2019 (forecast)

It is always difficult to predict what will cause the next upward move in bad debt charges for the banking sector. However, the banks’ high exposure to corporate loans and mortgages banks make the sector very sensitive to any events that negatively impacts the level of well-being of the Australian economy or that leads to any sustained downturn in property prices.

Banks are subject to regulatory and political uncertainty

In the last 2 years we have also seen a shift in stance by regulators and Government from an environment of de-regulation of the banking sector to re-regulation. We have fairly recently seen a coordinated response by regulators to enforce responsible lending standards and to ensure that banks are “unquestionably strong” by international standards. In 2018 apart from the well publicised Financial Services Royal Commission there are also other reviews being conducted across 8 government agencies focused on tightening controls and regulation of financial companies.

These reviews have unveiled instances of poor conduct and failures of process due to some irresponsible lending practices and general complacency within the banking sector. At best, the Banking sector will face an increasing burden of compliance costs and the need to rebuild their brands to reinstate trust. It also remains likely that we could see Parliament impose further constraints on home lending and perhaps introduce new levies and taxes on banks in the future.

As politicians and regulators review the findings of the Financial Services Royal Commission, it is hard to see the regulatory and political environment being as favourable as it has been, making it harder for Australia’s banks to grow their profits in future.

The lesson for investors is to consider their portfolio’s weighting to the Banking sector. While Australian banks remain very strong, profitable entities that have paid healthy dividends over a sustained period, but they are not without risk. While they remain worthy of inclusion in any well-structured portfolio, as with all investment portfolios, diversity is the key to managing risk.

In our view, investors with concentrated exposures to the big banks in their portfolios would do well to diversify beyond these to include attractively valued industrial companies with recurring earnings and a sustainable yield.

Source: Michael O’Neill – 19th October 2018