The contact team sport kabaddi that started in India, sepak takraw or kick volleyball that originates from Southeast Asia, dragon boat racing, taekwondo, five variations of karate and jet skiing were among the sports that featured in the 18th Asian Games held in Jakarta and Palembang in 2018. So too did the video games Arena of Valour, Clash Royale, Hearthstone, League of Legends, Pro Evolution Soccer and StarCraft II.

The rise of these six competitive online games or ‘electronic sports’ to inclusion in games affiliated with the International Olympic Committee netted China two and Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan and Korea one gold each, though these ‘esports’ victories didn’t count towards the overall tally won by China because these competitive video games only had ‘demonstration’ status.[1]

Medal status was promised for the 2022 Asian Games amid talk that esports could be included in the Summer Olympics before too long, given their appeal to younger generations who spend countless hours playing online games, many of which are free to play.

And why wouldn’t esports deserve Olympic status. Such is the popularity of online games at an amateur level, professional esports have become a US$900 million industry that boasts an audience of 380 million people[2] where leagues abound, teams train, competition is intense and skill is paramount, even it lacks the “anchor of physicality” found in other sports, as the IOC puts it.[3] At the professional level, ‘first-person shooter games’, ‘multiplayer online battle arena games’ and ‘survivor games’ – to describe just three types of esports – are performed in front of thousands of cheering fans. While the rounds of the League of Legends World Championship in 2018 only attracted meagre audiences, the final streamed to about 200 million viewers worldwide,[4] up from 60 million in 2017.[5] That’s nearly double the TV audience estimates for last year’s US Super Bowl[6] and bigger than the AFL Grand Final by a factor of 46.[7]

With such a crazed fan base who play and watch online games just for fun, the future of online gaming and professional esports seems assured. At the professional level, the activity enjoys sponsorships from the likes of Adidas, Nike and Under Armour. Media companies such as ESPN, Turner, Fox, NBC, YouTube and Amazon are jostling over media rights. Esports are backed by game makers such as Activision Blizzard, Electronic Arts, and Tencent’s Riot Games (owner of League of Legends) that offer millions of dollars of prize money for tournaments to promote their games.[8]

But Olympic medal status won’t come as quickly as promised, it seems. At the end of the Asian Games in October, IOC President Thomas Bach said esports wouldn’t achieve medal status at the next games because they promote “violence and discrimination. Egames where it’s about killing somebody, this cannot be brought into line with our Olympic values.”[9]

Therein lies the biggest challenge confronting the shooter and war-like video games that form a sizeable chunk of the US$138 billion online gaming industry[10] – their social costs. The image of the younger (mostly male) generation spending endless hours playing and watching anti-social, addictive and mindless online games laced with violence and death worries more than their parents. Some behavioural experts warn that these games (and non-competitive video games more broadly) cause mental, social and physical damage. Parents, schools, and health and other authorities are acting to limit the time youngsters spend on video games, to questionable effect so far, but such efforts may be just the start. While online games and esports are here to stay, their days of unhindered growth seem to have ended.

To be sure, parents and others think just about every new craze damages their kids and most prove innocuous. Many behavioural experts argue against the perceived social costs of video games. The debate is unlikely to be settled cleanly. Concerns about online gaming are focused on under-18s, so adults are free to play among themselves and follow the professional leagues. The restrictions are limited to a few countries though China, the largest online gaming market, is one of them. The social costs of the internet era extend well beyond online games. But the epicentre of the social costs of the internet could well be the millions of teenagers who spend hours killing and destroying onscreen in an age where toy guns are frowned upon in many quarters. Pressure is building for other countries to follow China and Korea in more forcibly controlling the content of online games and time spent playing them. As with any sport, stifle the amateur level and the professional level will flourish less than otherwise.

The esports ascent

In 2013, at two-all in the best-of-five final, Sweden’s Alliance and Ukraine’s Natus Vincere teams faced off in Dota 2’s annual championship for a US$1.4 million first prize. After about 40 minutes of defensive thrusts and then all-out attack by on-screen teams of mythical heroes, Alliance triumphed as an unexpected one million people watched Valve’s battle arena game online via a startup video site called Twitch.[11] In 2014, Amazon paid US$970 million for the video site filled with user-generated content that even four years ago was described as the world’s largest arena.[12]

No wonder. In the first quarter of 2018, Twitch, which dominates the streaming of online gaming including professional esports, with YouTube Gaming, averaged 953,000 ‘concurrent viewers’ worldwide (people watching at any one time), while YouTube Gaming averaged 308,000, according to Streamlabs.[13] Over 2017, Riot Games’s League of Legends matched its billing as the world’s highest-grossing online game title by being the most watched game on Twitch, amassing more than 1 billion hours of viewing.[14] Fortnite, an online shooter-survival game with cartoonish, rather than macabre, characters and a last-person-standing-from-a-hundred island-based killathon only released in 2017, is likely to surpass all records, such is its popularity.[15] These numbers, of course, do not capture the time people spend playing online games among themselves.

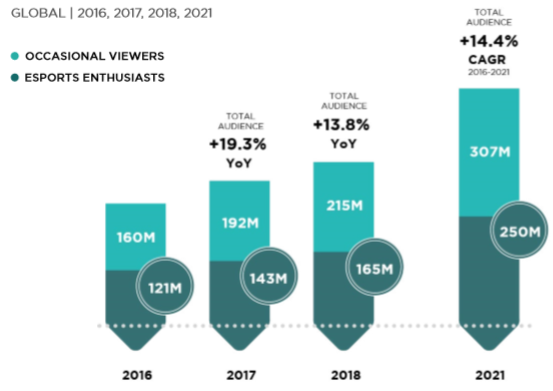

US-based esports consultancy Newzoo says even though the industry is probably 10 years away from becoming fully professional, the global esports audience reached 380 million people in 2018, up 14% on 2017, of which about 165 million viewers were ‘enthusiasts’.[16] At the professional level, Newzoo counted 588 major esports events were held in 2017, as fans paid US$59 million for tickets to watch players compete for US$112 million in total prize money over the year – first prize for the annual Dota 2 championship now stands at US$11.2 million, the total prize pool at US$25 million.[17]

Newzoo forecasts the professional esports industry to be worth US$1.4 billion by 2020 when tallying ticket sales, advertising and merchandising. If new formats and franchises woo more fans, Newzoo says the industry could be worth US$2.4 billion by 2020.[18] But for all its rapid rise and high hopes, the real and perceived social costs associated with online gaming may prevent professional esports becoming mainstream.

The ascent’s social costs

In June of 2018, the World Health Organisation issued the draft of the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases, its definitive list of diseases that can be treated, and declared a new complaint called “gaming disorder”. The mental disorder that afflicts some fraction of the countless people who play online games is characterised by “impaired control over gaming” of “sufficient severity to result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational” areas.[19]

The World Health Organisation’s bombshell gelled with long-standing criticisms that gaming at its most compulsive acts on the brain through dopamine, a chemical released by nerve cells that promotes repeat behaviour.[20] These people claim algorithms, behavioural techniques and rewards fine-tuned by ‘big data’ coalesce to hook players. The world body’s decision came five years after ‘internet gaming disorder’ was listed in the fifth edition of the US-based Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as an area of “much needed research”.[21] Some anecdotal evidence suggests many youngsters are addicted to online games and suffer depression and other disorders as a result.[22] Many parents will attest that even a few hours spent on, say, Fortnite will change their children’s behaviour, similar to how a sugar hit sparks up toddlers.

Such claims are not without critics, especially from within the online-gaming industry. Some psychiatrists say digital concerns are overblown.[23] The US-based Entertainment Software Association that represents US video-game makers called the world health body’s process “deeply flawed, and lacks objective scientific support” and said that gaming disorder should not receive official classification as a disease as is scheduled to occur in 2019.[24]

But the world health body’s official sanction would be no surprise because many mental experts warn that a wave of mental disturbances could be revealed among gamers in coming years. Australia’s government assessed in 2015 that internet use and online gaming were “highly problematic” for 3.9% of 11- to 17-year-olds, “affecting their ability to eat, sleep and spend time with family, friends and doing homework”.[25]

On top of addiction, some experts warn that the similarities of gaming and gambling addiction is enabling games such as Fortnite to use “predatory” techniques to entice money from youngsters hooked on “free games” via in-game purchases – though they would usually need access to the credit cards of their parents to buy anything.[26] US game maker Activision Blizzard, for instance, reaps more than half its revenue from in-game purchases, though much comes from Candy Crush.[27] Belgium’s Gambling Committee in 2018 declared that ‘loot boxes’ – a collection of random virtual rewards that gamers can win or purchase with cash while playing, where some items help them win – were gambling and banned them.[28] Other countries are said to be considering restrictions on loot boxes.

Rehabilitation for addicted youngsters is primitive and little help extends beyond parental control and the occasional support group such as Game Quitters, which was started by Canadian gaming addict Cam Adair in 2015 and has spread to 93 countries.[29]

South Korea is considered at the forefront of the addiction problem because online gaming moved from hobby to professional there earliest and has become popular enough to be judged a national pastime. In 2011, Seoul banned children under 16 going on gaming websites between midnight and 6 am. Three years later, however, the law was eased due to problems with enforceability. Even so, the restriction has caught on elsewhere.[30]

In 2017 in China, which overtook the US as the world’s largest game market in 2016, Tencent announced it would limit to one hour the amount of time children could spend playing its top-grossing Honour of Kings, a multiplayer battle game that is China’s most popular video game.[31] Tencent acted after the People’s Daily newspaper controlled by the Communist Party called the game a “poison” and said greater regulation of social games was needed.[32]

Sure enough in 2018, Beijing halted new game approvals for nine months, reduced the number of new online games to be approved in coming years and tightened control over game content including blocking Tencent’s Monster Hunter: World game for being too gory. Beijing also blamed short-sightedness among 450 million Chinese in part on excessive screen time, a meaningful part of which is spent on online games.[33]

Online gaming is also curtailed when authorities take steps against excessive general online use. The New South Wales government in December announced it was banning mobiles in public primary schools and giving public secondary schools the option to prohibit them, measures the opposition supported.[34] In France, a law banning mobile phones in schools took effect in September. [35] While such moves are not aimed at online games per se, they will limit the time spent on them.

Such efforts to curtail internet use among the young is shaping as a test of how society might evaluate the social costs of this online age. Where esports stand in terms of Olympic status could well be an indicator of the extent of that effort.

By Michael Collins, Investment Specialist

Esports audience is growing across the globe

Source: Newzoo. 2018

[1] For the results, see: Asian Electronic Sports Federation. ‘Road to Asian Games.’ aesf.com/Road-To-Asian-Games-2018/index.html

[2] Newzoo. ‘Free 2018 global esports market report.’ 21 February 2018. resources.newzoo.com/hubfs/Reports/Newzoo_2018_Global_Esports_Market_Report_Excerpt.pdf?hsCtaTracking=eefc7089-ed69-4dee-80ab-3fc9c6a4cba0%7C09cbff14-6fda-41d8-ab5a-a70c146be2cc

[3] International Olympic Committee. “looking to the future of sport and the games.’ 8 October 2018. olympic.org/news/looking-to-the-future-of-sport-and-the-games

[4] ESC. ‘Worlds 2018 – 200 million viewers at once.’ 4 November 2018. esc.watch/blog/post/worlds-2018-final

[5] Dot Esports. ‘The League of Legends Worlds final reach 60 million unique viewers.’ 17 November 2017. dotesports.com/league-of-legends/news/lol-worlds-final-viewership-18796

[6] Nielson. ‘Super Bowl LII draws 103.4 million TV views, 170.7 million social media interactions.’ 5 February 2018. nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2018/super-bowl-lii-draws-103-4-million-tv-viewers-170-7-million-social-media-interactions.html

[7] AFL. Classic grand final draws 4.3m television viewers.’ afl.com.au/news/2018-09-30/classic-grand-final-draws-43m-television-viewers

[8] The ‘partnership’ between the Asian Olympic Committee and Alisports, the sports arm of Chinese online retail company Alibaba, helped cement the committee’s decision to include esports in the 2018 Asian games.

[9] Associated Press. ‘Bach: No Olympic future for esports until ‘violence’ removed.’ 1 September 2018. apnews.com/3615bd17ebb8478ab534691080a9a32a. See also: International Olympic Federation. ‘Communique of the Olympic Summit.’ 28 October 2017. olympic.org/news/communique-of-the-olympic-summit

[10] Newzoo. ‘Mobile revenue accounts for more than 50% of global games market as it reaches $137.9 billion in 2018.’ 30 April 2018. newzoo.com/insights/articles/global-games-market-reaches-137-9-billion-in-2018-mobile-games-take-half/

[11] The Verge. ‘Field of streams: how Twitch made video games a spectator sport.’ 30 September 2013. theverge.com/2013/9/30/4719766/twitch-raises-20-million-esports-market-booming

[12] The Wall Street Journal. ‘Amazon to buy video site Twitch for $970 million.’ 26 August 2014. wsj.com/articles/amazon-to-buy-video-site-twitch-for-more-than-1-billion-1408988885

[13] Streamlabs. ‘Tipping up 33%, Twitch viewers up 21%, Fortnite dominates – Q118 Streamlabs report.’ 26 April 2018. streamlabs.com/tipping-up-33-twitch-viewers-up-21-fortnite-dominates-q118-streamlabs-report-52f60450af5a. On any day in 2018, Twitch had about 15 million unique visitors watching and chatting about videos. Figures sited for January 2018 by Macquarie Research show Twitch averaged 962,000 concurrent viewers over January compared with 885,000 for MSNBC and 783,000 for CNN. StreetInsider.com. ‘Amazon’s (AMZN) Twitch is bigger than CNN – Macquarie.’ 13 February 22018.

[14] Newzoo. Op cit. Pages 25 and 26.

[15] On Twitch.tv on 26 October 2018, for instance, 137,716 people were viewing Fortnite compared with 110,479 watching Red Dead Redemption II, 90,584 for Call of Duty: Black Ops, 57,631 on League of Legends and 39,464 viewers ‘just chatting’.

[16] Newzoo. Op cit. Page 11

[17] Dota 2. ‘The international Dota 2 championships.’ dota2.com/international/overview/

[18] Newzoo. ‘Newzoo: Global esports economy will reach $908.6 million in 2018 as brand investment grows.’ 21 February 2018. newzoo.com/insights/articles/newzoo-global-esports-economy-will-reach-905-6-million-2018-brand-investment-grows-48/

[19] World Health Organisation. ‘Gaming disorder. Online q&a.’ who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en/

[20] See abstract of study on the US National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health website. ‘Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction.’ 2009. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Brain+activities+associated+with+gaming+urge+of+online+gaming+addiction

[21] Society for the Study of Addiction. Addiction online publication. Editorial. ‘Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5.’ 13 May 2013. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.12162

[22] For one such study, see: Jean M. Twenge and W. Keith Campbell. ‘Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study’ published in Preventive Medicine Reports. Available online 18 October 2018. sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211335518301827

[23] See, Richard A. Friedman, a psychiatrist. ‘The big myth about teenage anxiety.’ The New York Times. 7 September 2018. nytimes.com/2018/09/07/opinion/sunday/teenager-anxiety-phones-social-media.html?em_pos=large&emc=edit_ty_20180907&nl=opinion-today&nlid=79468630edit_ty_20180907&ref=headline&te=1

[24] Entertainment Software Association. Media release. ‘Preeminent researchers and scientists oppose WHO’s proposed video game action.’ 1 March 2018. theesa.com/article/preeminent-researchers-scientists-oppose-world-health-organizations-proposed-video-game-action/

[25] Australian Department of Health. The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing.’ 2015. Page 24 of Word version. health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-m-child2

[26] See editorial in Addiction, a publication issued by the Australian-based Society for the Study of Addiction. Predatory monetization schemes in video games (e.g. ‘loot boxes’) and internet gaming disorder. Daniel King and Paul Delfabbro. 28 June 2018. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/add.14286

[27] Activism Blizzard. Quarterly results. ‘Investor summary.’ investor.activision.com/static-files/ddaeafa3-bfc1-474b-b6a9-c5daaf20fa95 and “Slide presentation’. investor.activision.com/static-files/80b94f0b-2ec2-48aa-a826-40077312a712

[28] BBC News. ‘Video game loot boxes declared illegal under Belgium gambling laws. 26 April 2018. bbc.com/news/technology-43906306

[29] To find out more, go to: gamequitters.com/

[30] Teenagers were using the national ID numbers of their parents to log onto these websites. The Wall Street Journal. ‘South Korea eases rules on kids’ late night gaming.’ 2 September 2014. blogs.wsj.com/korearealtime/2014/09/02/south-korea-eases-rules-on-kids-late-night-gaming/..

[31] Kids under 12 were limited to one hour a day and banned from 9 pm; those aged from 12 to 18 years were restricted to two hours a day. Reuters. ‘China’s Tencent to limit play time of top-grossing game for children.’ 3 July 2017. uk.reuters.com/article/us-tencent-games-idUKKBN19O0K0

[32] Reuters. ‘China communist party mouthpiece slams Tencent game; shares slide.’ 4 July 2017. reuters.com/article/us-tencent-games/china-communist-party-mouthpiece-slams-tencent-game-shares-slide-idUSKBN19P1F0

[33] ChinaDaily. ‘Students’s poor eyesight catches eyes of Chinese leadership.’ 7 June 2018. chinadaily.com.cn/a/201806/07/WS5b181f8fa31001b82571e895.html

[34] ABC News. ‘Mobile phones will be banned in NSW primary schools from next year.’ 13 December 2018. abc.net.au/news/2018-12-13/nsw-phone-ban-aims-to-reduce-bullying/10612950

[35] Agence-France Presse. ‘Phone ban rings in new French school year.’ 3 September 2018. afp.com/en/news/205/phone-ban-rings-new-french-school-year-doc-18s6tw4

Source – Magellan, Michael Collins